A review by Elsabé Dixon

Neville Barbour states:

Blessings in Gray “is a visual exploration of the narratives that define us. It explores what it is to be human and remarks on the ambivalence of that perspective. Neville explores how conflict can take us out of our comfort zone, yet become a force for change.”

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT STORY IMAGES

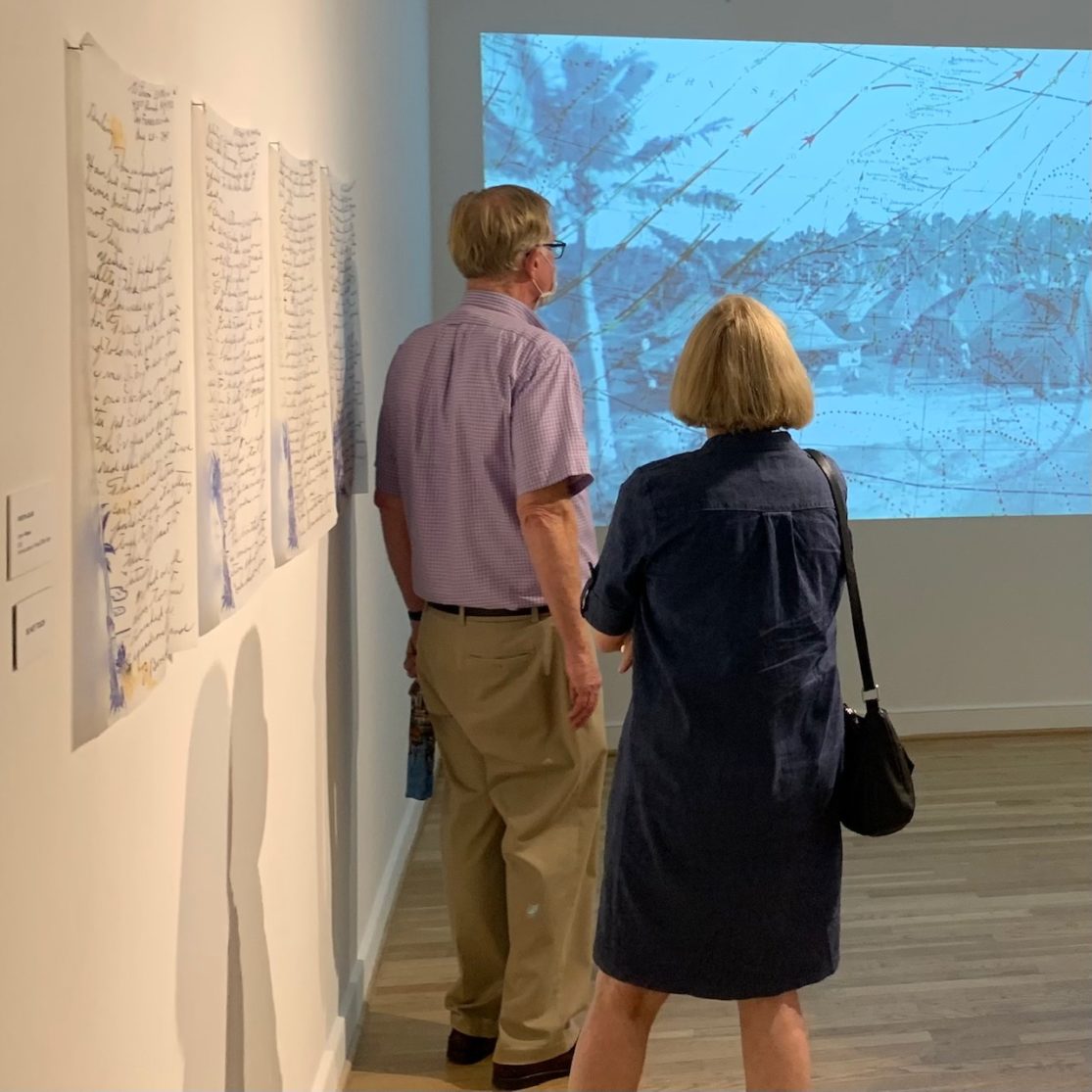

Every Image tells a story, but the good stories sometime need more time and attention to unfold fully. On a winter Friday afternoon in February of 2023, I spoke to Neville Barbour about the nine realistic figure drawings in his solo show at the Hillyer Gallery in Washington, DC. Each drawing seemed to hold complex symbols one could recognize, but the arrangements seemed to have a structure that made what you were looking at almost “abstract”.

A figure with angel wings, standing against the backdrop of a large detailed moon is simply called Monday, and Barbour explains that he has just become a father, and that having a child makes Monday more palatable. I did a double take… how does that statement connect to a mystical angel winged figure standing as if on a stage in front of a large projection of the moon with its pitted and cratered surface? The detail was exquisite, but what is the meaning exactly? A mixture of satellite imagery, with what looks like a historic priestess figure from an old opera photograph and the Art Nuevo wings from a stained glass window were the only references I had in front of me. Like a random but complex dream sequence/Dada image, perhaps what Barbour is saying is that one should not look at his images as you look at a Dutch still-life with defined and absolute symbols, but instead take an emotional stance. How does the title, Monday, and this winged figure against the backdrop of the moon resonate with YOU, the viewer?

I was curious – where would this conversation to clarify meaning lead? The second image we both looked at was Trap Wednesday. A masked African American male figure sits on a white throne with a black crow on his shoulder and horns, sticking out from under a long white beard. His fingers and neck is adorned with gold and the word “love” is formed on the right hand, and the word “hate” is formed by the rings on the left hand. A spear with an engraved face, leans up against the left leg of the throne. Next to the figure sits a large, hairy dog. Again, Barbour was very forthcoming about being an African American male artist in DC, and that in being so there is always the question around the philosophical statement of “doing the right thing.” He said he based this seated character loosely on Spike Lee. Behind the seated figure is what looks like an Aztec or Mesopotamian Symbol in gold.

St George the Dragon depicts an equestrian figure riding not a horse, but an African steer. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, George’s slaying of the dragon may be a Christian version of the legend of Perseus, who was said to have rescued Andromeda from a sea monster. It is a theme much represented in art, the saint frequently being depicted as a youth wearing knight’s armor with a scarlet cross. While Barbour depicts the rider’s lower half as a replica of the medieval armor of St. George, the top half reveals a bear chested rider with patterned dots often associated with tribal coming-of-age rites. This mixture of West African mythology and an equestrian war figure, or Saint-to-stave-off-evil, can become a nuisance during times of peace, stated Barbour. And I was reminded again not to tag the symbols as real meaning, but to glide on them as clouds float across a horizon.

You Remind Me depicts a beautiful, professionally dressed, African American seated female figure, with a fox fur around her neck. She is placed in front of a traditional enlarged checkered pattern. This, Barbour claims, is a dialogue between generations. Old photographs, Barbour says, often make one recall those who live in the present. Perhaps the most compelling drawing in this series is a drawing of six children. Five small black boys stand in the background, while a young girl with a patterned dress curls up with two muzzled hyenas looking straight at the viewer. The title, Lord of the “Flys” conjures up the title of William Golding’s novel. Barbour discloses that he grew up surrounded by strong female figures. “Hyenas are a matriarchal symbol and moves away from the concept of the patriarchal lion. This animal changes the viewpoint. Expands one’s perspective,” he says.

Fisherman of Souls, depicts an old man in a triangle looking straight at the viewer, with a landscape in the background and two abstract white circles floating in the foreground toward the left and the right of the old man. Two heads (represented by the circles) – New Baby (Personal experience) – Old Man (Perhaps, a way of looking back at the Old Year and looking toward the New Year, 2023). Idia, shows a young girl with eyes diverted. Barbour says he has become fascinated by the role Africa played in participating in the slave trade. “We live in a society where not everyone can win, where there is no good choice,” says Barbour. Salt, is named for the thing that allows us to “taste”. Far from the “Morton’s Salt Girl” in a raincoat under an umbrella, this drawing depicts a sultry and confident young lady in cascading silks, shading herself from the African sun. The next drawing, Janus, depicts the Roman God as an African American man in medieval armor. Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings.

Every drawing in this exhibition holds known symbols, but they become plastic and ephemeral. They are not static, but instead become less concrete and more malleable. In many ways, these drawings turn on its head the way we look at figurative work. It takes the images that we see, and the meaning we tie to it, and push it into the background. These figurative images – that reiterate symbols, pushing at the outer limitations of symbols and all the multiple meanings they can hold – translate into widening perspectives and larger cultural doorways.

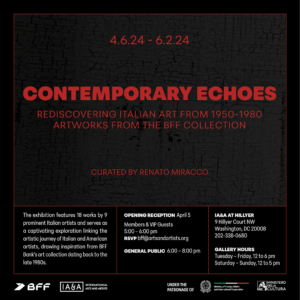

Neville Barbour

Archetypes

March 4-April 2, 2023

IA&A at Hillyer

To learn more about the artist visit nevillebarbour.com