What is your favorite thing people usually don’t notice?

What’s one of the most surprising materials used in the work?

What is a question you like to ask visitors viewing your work?

How do you want people to approach your art?

www.jgklausner.com

Art and the Dialectic of Possibility

by Timothy Brown, Hillyer Director

Elaine Qiu, Kim Richards, and Alexandra Chiou are three solo artists who offer a dialectic of possibility when faced with difficult moments in life. Dialectics start with oppositions that can leave us at an impasse, but each artist finds a way to work through challenging situations by finding peace through personal and collective reflection, guidance when life is unbearable, and joy when overwhelmed by loss.

Elaine Qiu in her exhibition “Every Place We’ve Been” embraces the duality of personal and collective loss, using scrolls and overlapping narratives to unite us across boundaries, while providing space for visitors to grieve and interpret meaning in their own way. As the artist states:

“I create works not just to express but to connect. I am interested in exploring dichotomies, such as power and vulnerability, reality and fiction, rebirth and decay, mystery and conviction, belonging and displacement.”

The liminality of the in-between space that Qiu alludes to is an invitation for viewers to connect across time and space. Scrolls are hung from the ceiling in undulating patterns that make it difficult to determine where the story begins or ends. The binary framework of the personal and the collective is reflected in her use of translucent paper that is painted on both sides. The scrolls thus serve as intersections, spaces where “verso” and “recto” merge, but which are revealed as a shared space of infinite possibilities.

“I want to invite the visitors to reflect on the fluid and dynamic essence of time and identity, and discover that the past is not fixed but a narrative in constant revision.”

In her exhibition “Into the Wilderness,” Kim Richards identifies the universal human condition of hopelessness and/or “impossible situations” we find ourselves in, and offers Biblically inspired paintings to remind us that we are not alone—God is there to lead us and help us find peace.

Most of the paintings feature a solitary figure, a young African American woman (her daughter in real life), who at first appears lost, alone, or abandoned to her own thoughts. The viewer may sense that there is an opposition at work that separates the subject from her objective conditions—a state of mind that places her “in the wilderness.” Similar to the liminal space in Qiu’s work, Richards employs the use of symbol and metaphor to extend the narrative. For example, in her painting “Rest,” Richards includes a raven and a rotten bag of fruit. The raven represents God and the holy spirit, and the fruit serves as a metaphorical way of laying down our burdens. Through these juxtapositions, the solitary figure is guided beyond the finitude of her corporeal existence by the everlasting presence of the holy spirit. As the artist states:

“The paintings in this exhibition embody a narrative of being called by God to help us face the unexpected challenges that lie ahead, so that we can travel through the wilderness, restored and at peace.”

In her exhibition, “Remember/Renew,” Alexandra Chiou celebrates the life and legacy of her late father and her healing journey after his passing. The challenge for Chiou is giving material form to abstract ideas and feelings such as hope, love, joy, and wonder when confronted with an overwhelming sense of loss. The passing of her father was compounded by her family’s decision to move to another location, leaving behind cherished memories.

Through her intricate use of painted cut paper, assembled in complex layers, Chiou uses her art to work through loss and separation by recognizing the dual value of memories and nature. In her piece, “Rebirth,” Chiou recalls a moment in her father’s life when he immigrated to the United States from Taiwan. Recognizing the fluid, boundless, and courageous nature of her father’s migratory experience, Chiou sought in this work to capture movement and transformation. Similar to Richards’s quest for peace, Chiou finds tranquility in the resuscitation of memories and their realization through nature-inspired, abstract forms. As the artist states:

“I hope that viewers can come here and find a sense of healing and a sense of stillness. Also I hope that viewers just remember to be kind to themselves and to celebrate life and all the small moments, big moments, and everything in between.”

The artwork by Elaine Qiu, Kim Richards, and Alexandra Chiou offers a dialectic of possibility that transcends trauma, loss, and abandonment. Through their art, viewers discover peace and beauty amid the “wilderness” that is encountered in our personal and collective experiences.

Newly Selected Artists: Elaine Qiu, Kim Richards, and Alex Chiou

March 2–March 31, 2024

An interview with Tim Brown, Hillyer Director

(TB):

Your work explores liminal spaces between presence and absence, representation and abstraction. What can you tell us about the painting “Crossing” as an embodiment of this kind of in-between space?

(EQ):

“Crossing” is part of the ongoing “inner-scape”series that explores the intricacies of threshold moments in life. Threshold typically takes the form of ambiguous spaces or moments: the interplay between light and dark, the cusp of dawn and dusk. This series’ paintings are all balanced on the brink of coming together and falling apart. I’m interested in these moments, because they are electrified with possibilities, embodying the process of transitioning into a new reality.

The relationship of presence and absence is explored on both a psychological and a visual level. “Crossing” creates an environment or scene that you almost find yourself entering. Yet, when we go closer, the physicality of the canvas and the paint dispel both the visual illusion and the constructed reality in our minds. It calls our attention to the bond between the sociopolitical, psychological, physical and physiological spaces we inhabit and the richly textured terrain of our inner landscape.

As I paint, I condense numerous dimensions onto the canvas, creating the illusion of gazing through multiple windows into infinite worlds at once. It mimics how our memory functions:a blended recall simultaneously pulls snippets from various timeframes to form a seemingly cohesive, although not always accurate, representation.

I make my paintings not only about something, but also about being something–each of my paintings exists as its own entity. I believe art can offer an encounter that brings forth revelations. These revelations can be transformations not unlike spiritual experiences.

Elaine Qiu, Crossing, 2022, enamel and acrylic on canvas, 84 x 86

(TB):

Renée Stout has noted that “stillness” as a concept reflected in her exhibition “The Oracle Said “Be Still” can be both passive and active. Would you describe your painting as cross section of those two ideas?

(EQ):

The pandemic brought about a global pause, and this involuntary stillness was thrust upon the masses. The stillness brought forth introspection, asking individuals to ponder their role and relevance in a world that seemed suddenly unfamiliar.

A pandemic painting, “Crossing” explores the dual stillness that Renée Stout mentioned. Just like the pandemic experiences of many, my past few years have also been filled with surprises, losses, and restructuring. I spent countless hours in the studio reflecting on my father’s final years and his passing. Much of my work from this period emphasizes the fading of things, the conclusion of various aspects of life, and the elusive, intangible aspect of our existence. Viewers have repeatedly highlighted the palpable stillness in “Crossing”: while the imagery and brushstrokes appear distraught and fragmented, they seem frozen in time. Much like the eerie silence before a storm and the desolation that follows a flood, the stillness shows up through these liminal moments in the painting in the form of waiting or listening. Only within the static silence do we allow the voice of uninvited questions to grow louder. After the stillness in the studio, my paintings always emerge as questions rather than answers. I found that the enforced quietude of the pandemic and the deliberate calm sought through art had, in tandem, guided me toward complex, nuanced questions that resist simplistic answers, questions that disturb, intrigue, evolve, and expand.

Some storms invigorate life in their aftermath, while others clear away the outdated and broken, but invariably, something is often left in their wake—the foundation of the new life. I hope that the questions born from the quiet moments of the pandemic years will actively and consciously guide us as we move forward in the remaking of the world.

(TB):

“Crossing” employs the use of one-point perspective. Yet, in the context of liminality, this point in space can also be viewed as temporal or indeterminate. What did you have in mind by using this compositional device?

(EQ):

One-point perspective is a frequently used art device in traditional Western paintings, particularly court and religious art works.It has almost become synonymous with authority, conventions, and predetermined truth.

At first glance, “Crossing” seems to embrace the classic one-point perspective, with its vanishing point drawing the viewer deep into the canvas, lending the painting both depth and realism. Yet the artwork subtly incorporates multiple perspectives. I intentionally kept these deviations to a minimum, making them discreetly interwoven throughout the painting. This nuanced approach invites viewers to reconsider their perceptions of reality and challenge the reliability of pre-established truths. The encounter with the painting affirms that what we see and know are simply slices of a more complete, comprehensive reality. It allows us to contemplate the unseen forces and overarching patterns at play. I believe such a vantage point offers solace and refuge from the tumult and chaos happening right now.

This moderate method of distortion also suggests that embracing differences doesn’t necessarily mean overturning established systems or norms entirely; rather, minor adjustments or small accommodations can lead to a more inclusive and harmonious collective existence.

(TB):

What is most evident about “Crossing” is the vibratory surface of the painting that shimmers like planes of darkness and light. Is it your intention to exploit the interplay of these opposing values?

(EQ):

Everything is a phenomenon of energy. The flow of energy, by its very nature, requires a preexisting polarity, such as high and low, or hot and cold.The interconnectedness of opposites has persistently emerged in my work. I have made monochromatic works. The interplay of lights and darks is not simply a matter of aesthetics; it’s an exploration of the inherent dualities within nature and the human spirit. I often contemplate juxtaposed realities: power and vulnerability, rebirth and decay, life and death, sorrow and joy, mystery and conviction, as well as the far and near enemies of these notions.

There is an old Chinese saying: Cherish the shadow and uphold the light(知陰守陽). Only by recognizing one’s own darkness can one see the light in others. By acknowledging our limitations, we pave the way for exploring greater possibilities. This exploration becomes particularly poignant when considering the contradictions in our human experience, especially in an era dominated by information silos and echo chambers. Embracing dissonant thoughts and clashing convictions might offer profound insight as we confront the great divide in our contemporary social-political landscape.

(TB):

It is quite interesting to view your painting alongside works by Cianne Fragione, Ellyn Weiss, Trevor Young, Sharon Farmer, and Joyce Wellman. Do you recognize some commonalities in their work?

(EQ):

In the exhibition, Renée Stout creates a contemplative space for viewers to revisit the stillness that permeated the pandemic. During the pandemic, even though there were other people around, like family members or even a pet, the truth is that each of us navigated this shared experience on our own. In reality, this is also how we navigate our individual lives—alone. Almost every piece showcased in this exhibition was born out of solitude.I am interested in painting the unspeakable and the unnamable—the things that keep us awake at 3 a.m.—the grief, the longing, the joy tinged with pain, and the sweet sorrow—the things that torment us while sustaining us most. To echo James Baldwin, “these were the very things that linked us to every living soul, past and present.”

Moving through the exhibition, I felt a familiar resonance in the works of my fellow artists. Each piece emanates its own unique radiance, encapsulating our individual triumphs and tribulations. Over the past years, we’ve navigated through calamities, dysfunction, and chaos. Many times, we had to stop and feel for the ground. But here, together, our artworks map out this cartography that reveals the edges and frontiers of our inner world as well as the ever-changing collective consciousness whose contours are formed by our stories told in silent studio hours and our stances held in stillness. It’s in this space that we come to an embrace, to a recognition of our common humanity, and to a glimpse of possibilities.

by Tim Brown, Hillyer Director

The exhibition “The Oracle Said ‘Be Still’,” curated by Renée Stout, on view at IA&A at Hillyer from October 7–October 29, 2023, embraces a paradox that recognizes the value of stillness without eliminating the possibility of “speaking truth to power.” The idea for the exhibition was taken from a print that Renée Stout worked on during the height of the COVID pandemic. The work was prompted by DC gallerist George Hemphill whose intention was to keep art alive and accessible during a time when people were less likely to engage with art. By evoking the oracle, Stout resonated with something happening in the universe that compels us to be still. In the work, Stout depicted the oracle in the form of a disembodied head with a speech bubble uttering the phrase that would later become the underlying concept for her exhibition.

The Oracle Said Be Still

Generally speaking, an oracle is a person or thing that provides insight into the future, a portal through which the gods speak to everyday people. Stout presented the oracle as an all-encompassing voice that compels everyone to hit a “reset button” and reflect on the challenges we face, so that we can act in a more informed way. During her conversation with Camille Brown, Assistant Curator at The Phillips Collection, Stout cited a passage from her notebook which guided her preparations for the exhibition:

“Life is fragile. Nature is fragile. Democracy is fragile. These truths can get buried behind the distractions and noise of daily life. One of the lessons COVID presented, which some people recognized while others did not, is that sometimes the universe needs for us to be still, so that we can take the time to ponder, become aware, and make valuable connections between events that are happening all around us that affect us all either directly or indirectly. Sometimes quiet is required to see clearly and listen intently, so that the universe can bestow its natural order upon things and restore the balance that it is always seeking to create. The oracle said, ‘be still’.”

While stillness is a focal point, Stout did not intend for it to be viewed in opposition to political action. As someone who is known for her political activism (if you follow her on social media), Stout views stillness as a liminal space, a spiritual, intellectual, and somatic space that is not dormant, but active—a wellspring from which human thought and action is made possible.

First and foremost, Stout is a practicing artist based in DC, so she set out to identify other artists in the area whose work embodied the same spirit and ideas she had in mind for the show. As someone described as a “do-it-yourself conjurer,” Stout’s approach to selecting artists was not unlike the “Spirit Detector,” a mixed media work she created in 2014. She “detected” the spirit of these fellow artists—root conjurors—who she felt had the capacity to give voice and visual form to the stillness that nurtures us through challenging times.

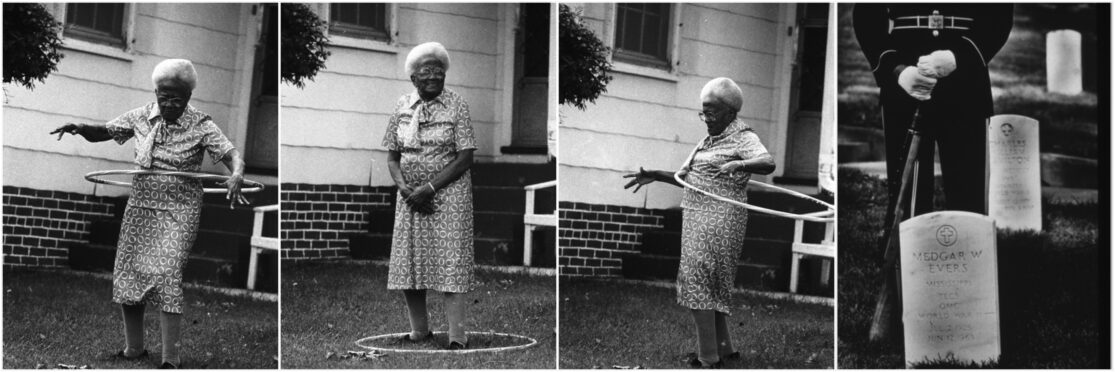

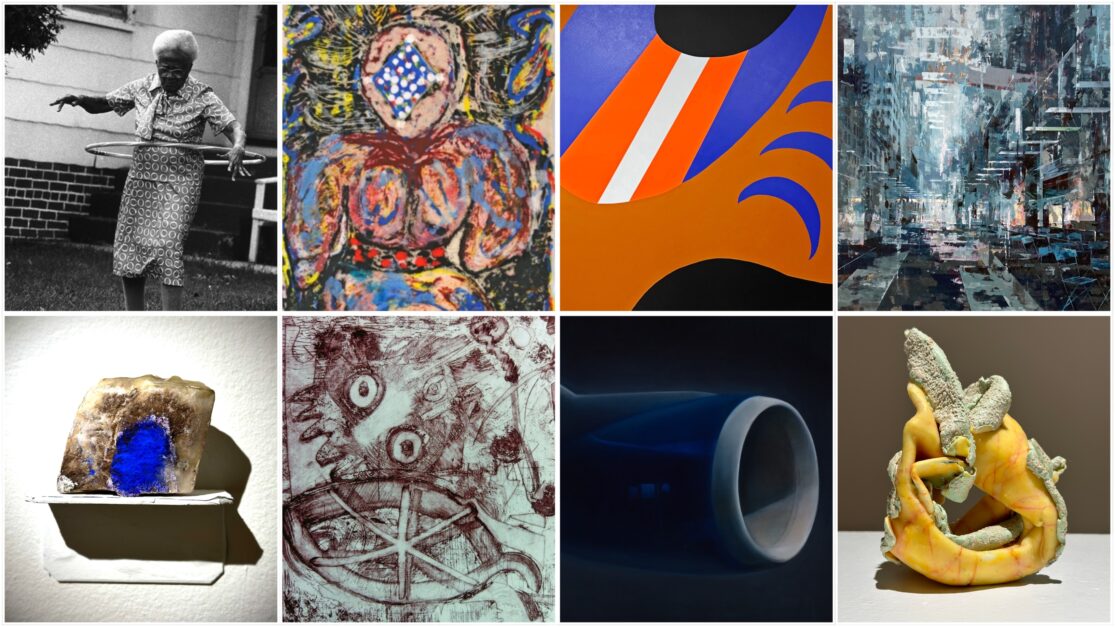

The exhibition features 8 artists: Sharon Farmer, Joyce Wellman, Ellyn Weiss, Elaine Qiu, Cianne Fragione, Cheryl Edwards, Adrienne Gaither, and Trevor Young. Stout chose four photographs by Sharon Farmer: three of Bernice Fergerson, and one with the grave of Medgar Evers. Stout described these works as bookends for the exhibition, symbolizing the cyclical nature of life and death, joy and sadness, undergirded by the silence of the human spirit to sustain us over generations. Stout also explains why Fergerson was chosen as the signature piece for the exhibition:

“One of the reasons why I picked this work was the synchronicity—her dress had all these O’s on it and then the hula hoop forms an O—she is the oracle.”

Sharon Farmer

Stillness and the oscillation between abstraction and material form is manifested in ways that vary in the works by each artist in the exhibition. “Crossing,” a painting by Elaine Qiu, reverberates with fractals of light that seem to break through the cacophony of societal noise, leaving us in the interstices of silence that compel us to be still amid the confusion. Cheryl Edwards is summoned into the stillness with “The Old Nubian” through her use of pulp painting, embedded with Mexican milagros metals to soothe the spirit and pave the way for self-decolonization. Cianne Fragione is inspired by “Fragments of Carrara” marble that embodies the primacy of hue and form that speak to you directly, uninterrupted by “noise” and artificial mark-making. Adrienne Gaither’s “Comin’ Thru” is part of a series called “Meditations on Brown,” color field landscapes that serve as a form of escapism as she reimagines a new place of possibility.

Sharon Farmer, Cheryl Edwards, Adrienne Gaither, Elaine Qiu, Cianne Fragione, Joyce Wellman, Trevor Young, Ellyn Weiss

Inspired by climate change, Ellyn Weiss’s “Form-Undentified Specimen 21” is a reflective response to ice receding in the north pole, using wax as a corollary to the inverse effect of flatness and its emergence as a rising man-made form. Joyce Wellman has two etchings in the show (“Third Eye” and “Untitled Sky”) that are created through stream of consciousness, conjuring in the process undersea creatures and a third eye with powers of perception beyond ordinary sight. And finally, Stout’s hoodoo premonitions led her to the work by Trevor Young. Young’s “Hub” explores the power of man-made things by taking them out of their context and re-presenting them as meditations on abstraction and mysticism.

Installation shots

One cannot fully understand Stout’s vision for the exhibition without seeing the works collectively in the space. The light throughout both galleries is toned down, as if immersed in islands of solitude, only to be summarily awakened by periodic flashes of light, color, texture, and form that guide you through the stillness and the impending forms of abstraction and figuration.

Through Stout’s careful planning of her exhibition, the oracle provides many opportunities to contemplate the value of stillness. Visitors are more apt to feel grounded after seeing the exhibition and better prepared to take on the noise that awaits us during these tumultuous times.

______

Author: Timothy Brown, Director, IA&A at Hillyer

Note: If you do have an opportunity to see the exhibition, visit our YouTube channel to hear talks by the artists and a conversation with Renée Stout and Camille Brown, Assistant Curator at The Phillips Collection.

An Interview with Advocate Member, Tiffany Chen

Tiffany Chen, Advocate Member

Tim Brown, Hillyer Director (TB):

Tiffany Chen (TC):

My profession is so DC!

I’m a federal government consultant. With two different business degrees (logistics, and international financial management), my day-to-day is focused on technical account management.

My personal interests are mainly the arts (collecting and creating), as well as my adorable puppy Ernest “Ernie” Hemingway, who is the cutest.

(TB):

(TC):

My art collecting began simply because I love art.

Attending the art fairs in New York: the Amory, Frieze, TEFAF, plus Art Basel, Art Basel Miami, Design Week Vienna, Venice Biennale, I began by acquiring pieces that caught my eye, but lacked a larger theme or purpose.

In 2018, while visiting the National Museum of Women in the Arts, I learned that 87% of all the artwork in American art museums were created by men!

That day, I decided to only collect from living female artists.

I began with signed originals, prints, and books from my favorite, established female artists, such as Judy Chicago and Donna Huanca.

Luckily, many of my closest friends are also amazing emerging artists!

Lillian Ling (poetry, multi-media embroidery, and graphic design), Sunbin Song (performance and multimedia), and Shannon Stichman (oil paintings), all create spectacular works, which I am blessed enough to sneak-peek and call dibs!

(TB):

(TC):

Thus far in 2023, I have acquired two pieces from Hillyer artists: the first from Elaine M. Erne and most recently, from Katherine Burling.

Elaine M. Erne’s pencil drawings are extraordinary, simultaneously other-worldly and every day; all meticulously hand-drawn, eerie, and brilliant. Her Instagram name is “lovedrawingbunnies” so Erne’s “Lovely Bunny” had to come home with me.

Katherine Burling’s mixed-media collages instantly drew me in at First Friday, where we spoke candidly about her art inspiration and creation. I love that her works are historical yet modern, appealingly comforting but deeply dark.

Both artists’ works portray different aspects of what it means to be a modern woman, a question I ask myself constantly. As an only child and only daughter, I find solace in this artistic sisterhood.

(TB):

(TC):

The Hillyer displayed itself to me as the Sphynx appears in the myths: by luck.

In college, I was fortunate to have had an amazing honors architecture professor, who opened the city’s doors to me. As such, Washington, D.C. was a familiar friend and I adored visiting the Phillips Collection for hours and hours.

Before one of these adorations, I happened to walk behind the carriage house, and there was the Hillyer! I walked in and was immediately impressed by the gallery’s dedication to curating and supporting emerging artists, and have returned every since… so for nearly 20 years.

(TB):

(TC):

At this point in my life, I am old enough, and brave enough, to know what I like.

I like the Hillyer!

From the amazing art, to the gallery space, to the people who breathe life into the organization, I feel at home here. Maybe because I’ve been hanging around the Hillyer for over a decade!

(TB):

(TC):

The Hillyer is a hidden gem.

“Selling” the Hillyer is easy. Centrally located in DuPont, the Hillyer is the perfect locale for my friends from all over the city to meet-up and experience amazing emerging art in a beautiful space, at one’s own pace. With a consistently full calendar of programs and events, the Hillyer combines beauty, ease, and comfort. An absolute dream!